Las mujeres y la historia del arte no han tenido una relación muy saludable, si queremos verlo de manera franca. Quienes se han encargado de escribir esa historia han dejado fuera de sus renglones a cientos de mujeres que se merecían esas líneas por propio derecho. Por ejemplo, si examinamos con atención libros tan canónicos como “La Historia del Arte” de E. H. Gombrich (Ed. Phaidon), que ha vendido más de ocho millones de copias durante cinco décadas y se ha traducido a más de 30 idiomas, veremos que en el libro no aparece una sola mujer artista hasta una de sus últimas ediciones, la edición número 10, cuando deslumbra entre sus páginas el trabajo de una grande: Käthe Kollwitz.

Women and the history of art have not had a very healthy relationship, if we want to put it frankly. Those who have been responsible for writing that history have left out hundreds of women who deserved those lines by their own right. For example, if we closely examine canonical books such as “The Story of Art” by E. H. Gombrich (Phaidon Press), which has sold more than eight million copies over five decades and has been translated into more than 30 languages, we will see that not a single female artist appears in the book until one of its latest editions, the 10th edition, when the work of a great artist dazzles within its pages: Käthe Kollwitz.

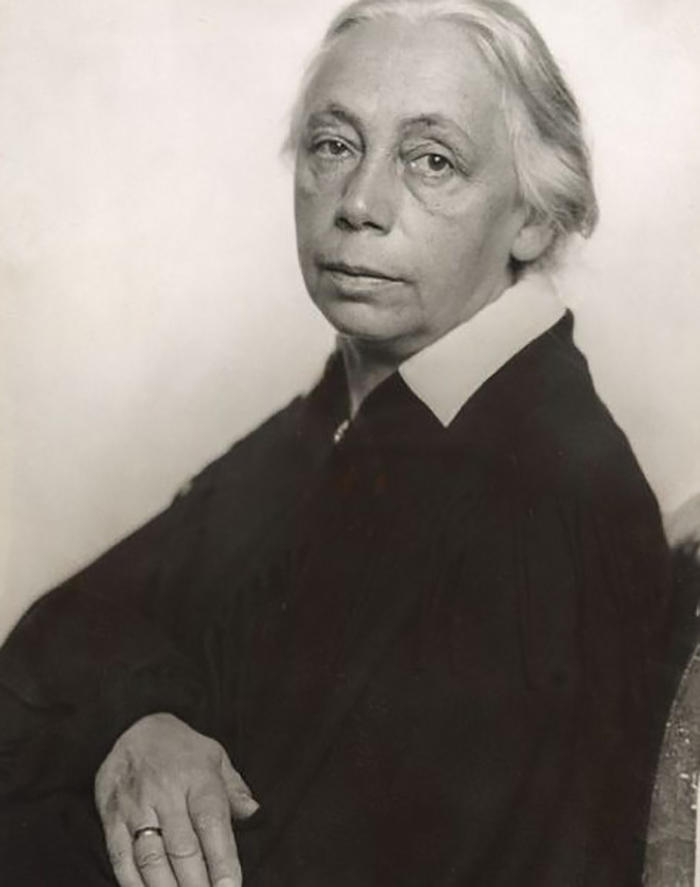

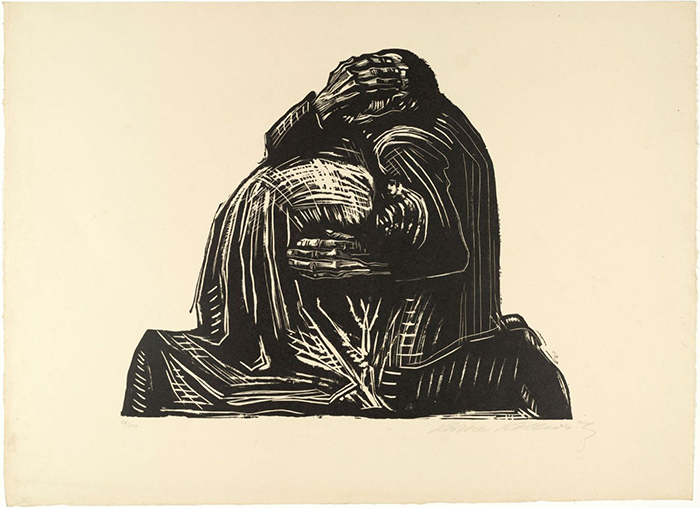

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), fue una artista alemana cuyo trabajo estuvo comprometido con los fenómenos sociales durante el siglo XIX, abrazando el expresionismo de principios del XX. Su obra es una exploración de las profundidades de lo humano, es decir, sus padecimientos como la angustia y la fragmentación de la psique, ocasionados por los grandes problemas que agobian al mundo: las guerras, la violencia, el hambre y, sobre todo, un tema que la obsesionó durante toda su vida: la muerte. Esta obsesión fue detonada por un suceso que la marcó desde joven, la muerte de sus dos hermanos. Kollwitz vivió con ataques de ansiedad, delirios y una condición que los psiquiatras han llamado “el síndrome de Alicia en el País de las Maravillas”, o más conocido como micropsia, que consiste en ver que los objetos varían de tamaño frente a sus ojos.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) was a German artist, whose work was deeply engaged with social phenomena during the 19th century, embracing early 20th-century expressionism. Her oeuvre is an exploration of the depths of human experience, particularly its sufferings such as anguish and the fragmentation of the psyche, brought on by the major issues afflicting the world: wars, violence, hunger, and above all, a theme that obsessed her throughout her life: death. This obsession was triggered by a tragic event that marked her from a young age, the death of her two brothers. Kollwitz lived with anxiety attacks, delusions, and a condition psychiatrist have termed “Alice in Wonderland syndrome,” better known as micropsia, where objects appear to change size before her eyes.

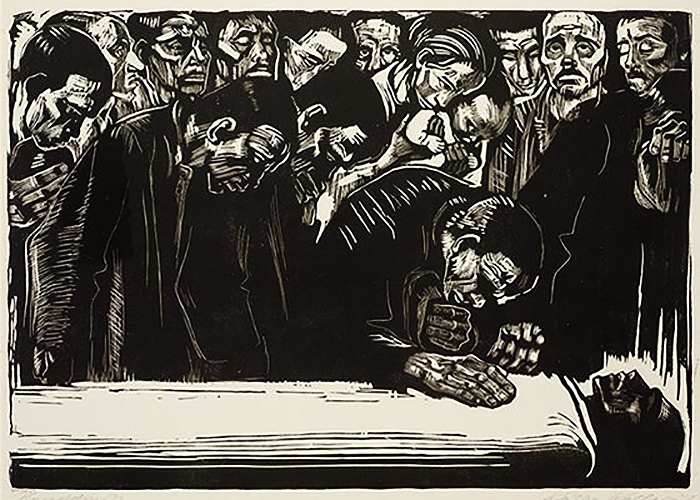

Estudió Artes en Berlín y Múnich, y conoció el mundo de la cultura y la élite en Alemania a finales del siglo XIX. Durante sus exploraciones artísticas, se dedicó a la pintura, pero se interesó más por las artes gráficas, donde el grabado se convirtió en su mejor herramienta de expresión. La fuerza expresionista gestual y la poderosa impronta de sus trazos y decisiones en cada línea de su trabajo la convierten en una artista respetada por sus colegas. En 1891 contrajo matrimonio con el médico Karl Kollwitz, con quien concibió a dos hijos que le fueron arrebatados en la Primera Guerra Mundial. De nuevo, la muerte asomó a su vida, y su trabajo se convirtió en un grito por la paz y la libertad, aunque esto le costara estar obligada a retirarse como académica de la universidad (entre 1898 y 1903 enseñó en la Academia de Mujeres Artistas de Berlín), y su trabajo fue prohibido por los abusos de los nazis.

She studied Arts in Berlin and Munich and immersed herself in the world of culture and the elite in Germany at the end of the 19th century. During her artistic explorations, she initially focused on painting, but became more interested in graphic arts, where printmaking became her primary tool of expression. The gestural expressionist force and the powerful imprint of her strokes and decisions in each line of her work made her a respected artist among her peers. In 1891, she married the physician Karl Kollwitz, with whom she conceived two children who were tragically taken from her during World War I. Once again, death cast its shadow over her life, and her work became a cry for peace and freedom, despite this leading to her forced withdrawal from academia (she taught at the Berlin Women Artists Academy between 1898 and 1903), and her work was banned due to Nazi abuses.

Su vida finalizó unos días antes del fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, y aunque durante su vida el suicidio pudo pasarle por la cabeza, logró superarlo mientras fue huésped del Príncipe Ernesto Enrique de Sajonia en el Castillo de Moritzburg. Ahora su obra es un legado que se resguarda en museos e instituciones como el Museo Käthe Kollwitz de Berlín, que cuida y divulga activamente su trabajo; así como otros museos del mundo, como el MoMA de Nueva York, que le ha realizado una exposición retrospectiva, la más grande en Estados Unidos en más de 30 años.

Her life ended just days before the conclusion of World War II, and although thoughts of suicide crossed her mind during her lifetime, she managed to overcome them while staying as a guest of Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony at Moritzburg Castle. Now her work is a legacy preserved in museums and institutions such as the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Berlin, which actively preserves and promotes her art work, as well as in other museums around the world like the MoMA in New York, which has hosted a retrospective exhibition, the largest in the United States in over 30 years.

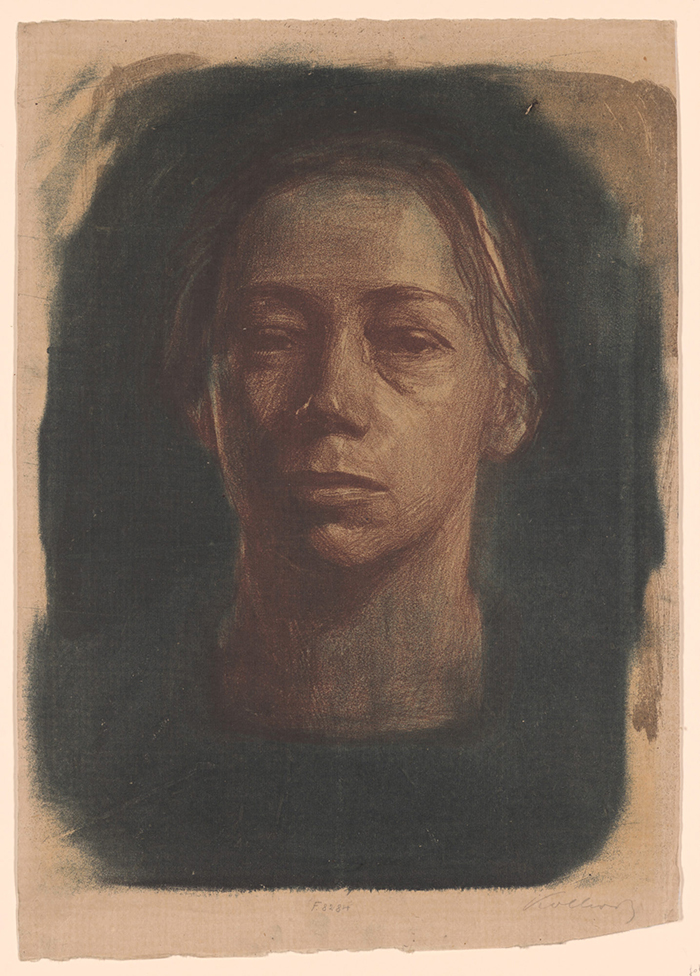

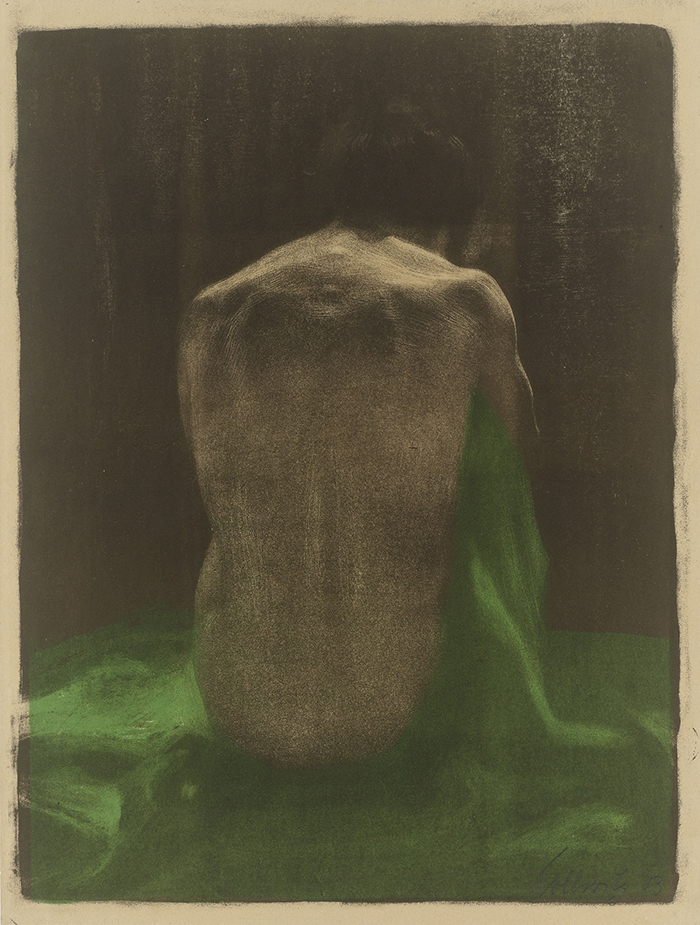

La exposición, titulada “Käthe Kollwitz”, presenta 110 ejemplos raramente vistos de sus dibujos, grabados y esculturas, extraídos de colecciones públicas y privadas. Organizada cronológicamente por Starr Figura, curadora, en equipo con Maggie Hire, asistente curatorial, la exposición rastreará el desarrollo de la obra de Kollwitz desde la década de 1890 hasta la de 1930, un período de agitación sin precedentes en la historia alemana, marcado por Los males sociales de la industrialización a fines del siglo XIX y los traumas de la guerra y la agitación política.

The exhibition, titled “Käthe Kollwitz,” features 110 rarely seen examples of her drawings, prints, and sculptures, sourced from both public and private collections. Organized chronologically by curator Starr Figura, in collaboration with assistant curator Maggie Hire, the exhibition traces Kollwitz’s artistic development from the 1890s to the 1930s, a period of unprecedented turmoil in German history marked by the social ills of late 19th-century industrialization and the traumas of war and political upheaval.