Venecia, 05.04.25

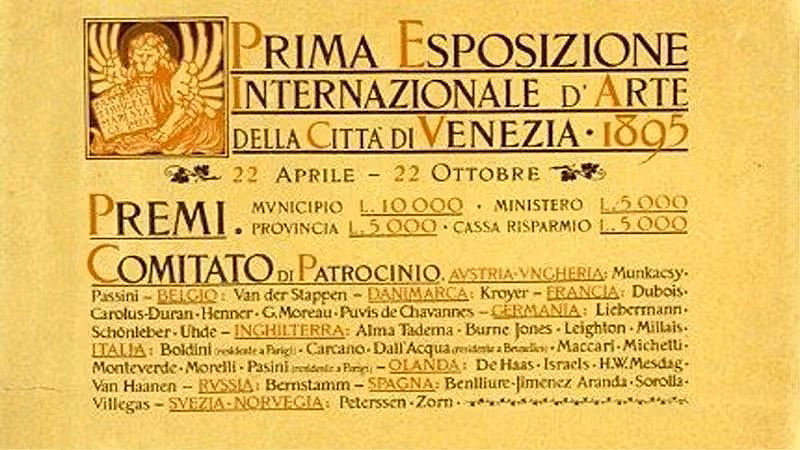

La Biennale di Venezia es uno de los eventos institucionales del arte más importantes y prestigiosos en todo el mundo, y como bienal de arte italiana, nació en 1895 con una primera Bienal donde se daban cita las artes decorativas. El 19 de abril de 1893, el ayuntamiento de Venecia fundó con un decreto la creación de la “Primera Exposición Internacional de Arte de la Ciudad de Venecia”, en honor a las bodas de plata de Umberto I y Margarita Teresa de Saboya. Se decidió adoptar un sistema de invitación, reservando una sección para artistas italianos y otra para artistas extranjeros. Y en este artículo revisaremos ese lugar icónico donde se ha realizado, desde sus inicios, esta prestigiosa bienal.

The Venice Biennale is one of the most important and prestigious institutional art events in the world. As an Italian art biennial, it was founded in 1895, with its first edition focused on the decorative arts. On April 19, 1893, the City Council of Venice issued a decree establishing the “First International Art Exhibition of the City of Venice,” in honor of the silver wedding anniversary of Umberto I and Margarita Teresa de Saboya. It was decided that the exhibition would follow an invitation-based system, with separate sections for Italian and foreign artists. In this article, we take a closer look at the iconic site that has hosted this renowned biennial since its inception.

Con su inauguración en 1893, la bienal abrió las puertas de los Jardines Napoleónicos en 1895. Los jardines fueron creados entre 1808 y 1812 durante la era napoleónica, cuando Napoleón Bonaparte ordenó la transformación de áreas pantanosas en jardines públicos, según el diseño del arquitecto Giannantonio Selva. Para la Bienal, se construyó rápidamente el Palazzo dell’Esposizione en los Giardini, diseñado por el arquitecto Enrico Trevisanato con una fachada neoclásica de Marius De Maria. Este edificio, inicialmente llamado “Pro Arte” y posteriormente “Italia”, fue inaugurado el 30 de abril de 1895 durante la primera “Exposición Internacional de Arte de la Ciudad de Venecia”, que atrajo a más de 224.000 visitantes.

With its founding in 1893, the Biennale opened the gates of the Napoleonic Gardens in 1895. The gardens were created between 1808 and 1812, during the Napoleonic era, when Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the transformation of marshy land into public gardens, following the design of architect Giannantonio Selva. For the Biennale, the Palazzo dell’Esposizione was swiftly built within the Giardini, designed by architect Enrico Trevisanato with a neoclassical façade by Marius De Maria. This building, initially named “Pro Arte” and later “Italia,” was inaugurated on April 30, 1895, during the first “International Art Exhibition of the City of Venice,” which attracted over 224,000 visitors.

El éxito de las primeras ediciones llevó a la construcción de pabellones nacionales dentro de los Giardini. Bélgica fue el primer país en erigir su propio pabellón en 1907, seguido por otros países europeos en los años posteriores encargando a arquitectos de renombre como Josef Hoffmann para que diseñaran espacios de exposición permanente, consolidando así el modelo de los pabellones que aún se utilizan para cada nación.

The success of the early editions led to the construction of national pavilions within the Giardini. Belgium was the first country to build its own pavilion in 1907, followed by other European nations in the following years. These countries commissioned renowned architects—such as Josef Hoffmann—to design permanent exhibition spaces, establishing the pavilion model that is still used today by each participating nation.

La edición de 1910 marcó un hito al presentar por primera vez artistas de gran renombre como Gustav Klimt, Pierre-Auguste Renoir y Gustave Courbet. Ese mismo año, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti manifestó su rechazo al evento arrojando panfletos en la Piazza San Marco, en un gesto provocador típico del futurismo. Además, una obra de Pablo Picasso fue retirada del salón español por considerarse demasiado transgresora para el público de la época. Más adelante, en 1922, España consolidó su presencia con un pabellón propio diseñado por el arquitecto Javier de Luque, aunque su fachada fue restaurada por Joaquín Vaquero Palacios en 1952. Desde entonces, este espacio ha acogido las obras de destacados artistas nacionales como Eduardo Chillida, Antoni Tàpies, Susana Solano, Santiago Sierra, Miquel Barceló, Dora García y Lara Almárcegui, entre otros.

The 1910 edition marked a milestone by featuring, for the first time, renowned artists such as Gustav Klimt, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Gustave Courbet. That same year, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti expressed his opposition to the event by throwing pamphlets in Piazza San Marco—a provocative gesture typical of Futurism. Additionally, a work by Pablo Picasso was removed from the Spanish Pavilion for being considered too transgressive for the audience of the time. Later, in 1922, Spain solidified its presence with a pavilion of its own, designed by architect Javier de Luque, although its façade was restored in 1952 by Joaquín Vaquero Palacios. Since then, this space has showcased the work of prominent Spanish artists such as Eduardo Chillida, Antoni Tàpies, Susana Solano, Santiago Sierra, Miquel Barceló, Dora García, and Lara Almárcegui, among others.

En 1991 con motivo de la V Exposición Internacional de Arquitectura de la Bienal de Venecia, el pabellón del libro fue diseñado por James Stirling, y fue situado en el espacio frente a la entrada a los jardines. Se trata de una construcción larga de una sola planta realizada con una estructura de metal y vidrio dividida funcionalmente en dos partes. La forma del Pabellón nos recuerda una estructura naval, a la que se superpone, en una duplicidad no resuelta, el tema simple de una cabaña.

In 1991, on the occasion of the 5th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, the Book Pavilion was designed by James Stirling and placed in the space opposite the entrance to the Giardini. It is a long, single-story structure made of metal and glass, functionally divided into two sections. The form of the pavilion evokes a naval structure, overlaid—somewhat ambiguously—with the simple silhouette of a cabin.

En 2009, el histórico Pabellón Central de los Giardini inició su transformación en una estructura multifuncional y versátil de 3.500 m², convirtiéndose en un centro de actividades permanentes y en un punto de referencia para los demás pabellones del recinto. Este proceso incluyó la incorporación de espacios concebidos por reconocidos artistas internacionales: Massimo Bartolini diseñó el Área Educativa “Sala F”, Rirkrit Tiravanija estuvo a cargo de la librería y Tobias Rehberger intervino la cafetería. La transformación concluyó en 2011 con la reorganización de las salas expositivas y del vestíbulo de entrada, consolidando así su nueva vocación como núcleo activo de la Bienal.

In 2009, the historic Central Pavilion of the Giardini began its transformation into a multifunctional and versatile 3,500 m² structure, becoming a hub for permanent activities and a point of reference for the other pavilions in the complex. This process included the integration of spaces conceived by renowned international artists: Massimo Bartolini designed the Educational Area “Sala F,” Rirkrit Tiravanija was responsible for the bookstore, and Tobias Rehberger intervened in the cafeteria. The transformation was completed in 2011 with the reorganization of the exhibition halls and the entrance lobby, thus solidifying its new role as an active nucleus of the Biennale.

Una parte importante del proyecto de recuperación consistió precisamente en la finalización de la restauración de la Sala Octogonal, iniciada por el Ayuntamiento de Venecia en 2006, con la recuperación de las pinturas de la cúpula de Galileo Chini de 1909 y con la restauración del aparato decorativo de las paredes y del pavimento de terrazo veneciano. El Salón, dotado de todos los servicios para la acogida del público, vuelve así a ser un punto de apoyo del Pabellón en forma de atrio monumental desde el que se accede a todas las nuevas áreas funcionales.

An important part of the restoration project was the completion of the Octagonal Room’s renovation, which had been initiated by the Venice City Council in 2006. This included the recovery of the 1909 dome paintings by Galileo Chini and the restoration of the decorative elements on the walls and the Venetian terrazzo flooring. Equipped with all the necessary public amenities, the hall once again serves as a key feature of the Pavilion, functioning as a monumental atrium that provides access to all the new functional areas.

Actualmente, los Giardini albergan 29 pabellones nacionales, cada uno representando a un país diferente y diseñado por arquitectos reconocidos, reflejando una variedad de estilos arquitectónicos que contribuyen al carácter único del lugar. A lo largo de los años, los Giardini della Biennale han evolucionado hasta convertirse en un símbolo de la Bienal de Venecia, consolidándose como un punto de encuentro esencial para el arte y la arquitectura contemporáneos a nivel mundial.

Today, the Giardini host 29 national pavilions, each representing a different country and designed by renowned architects. These pavilions reflect a wide range of architectural styles, contributing to the unique character of the site. Over the years, the Giardini della Biennale have evolved into a symbol of the Venice Biennale, establishing themselves as a key meeting point for contemporary art and architecture on a global scale.