“La mayor vocación de la fotografía es explicar el hombre al hombre”

Susan Sontag

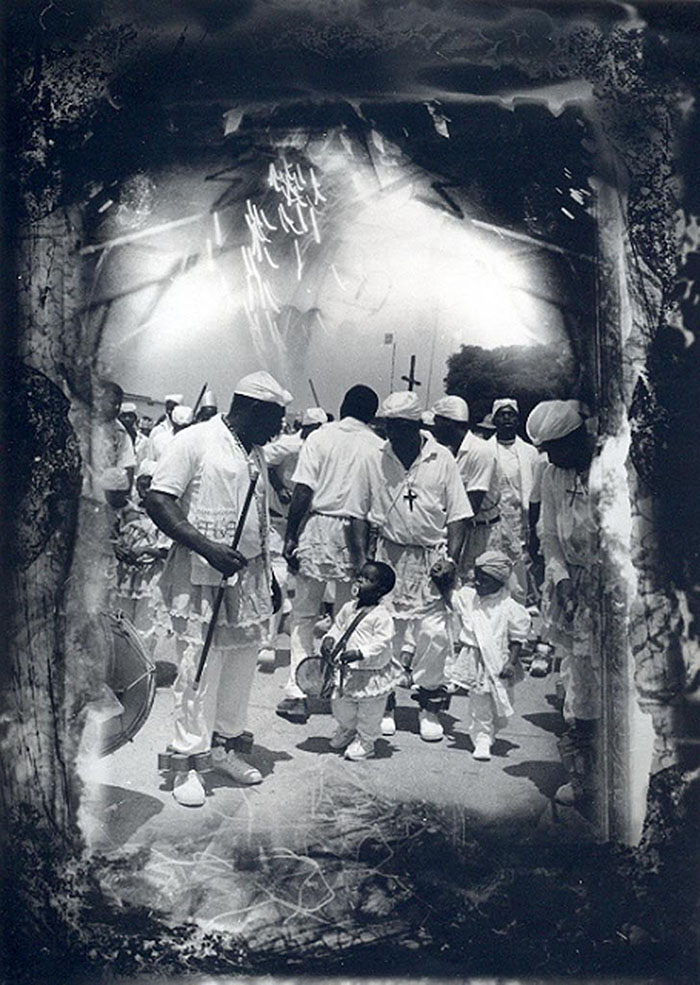

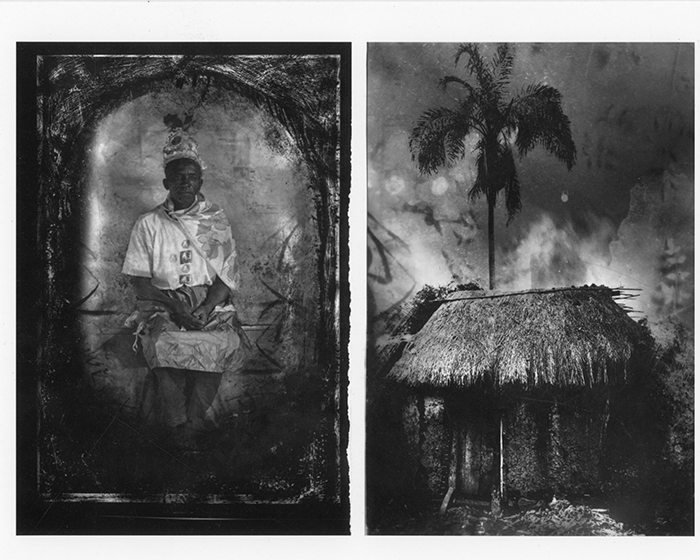

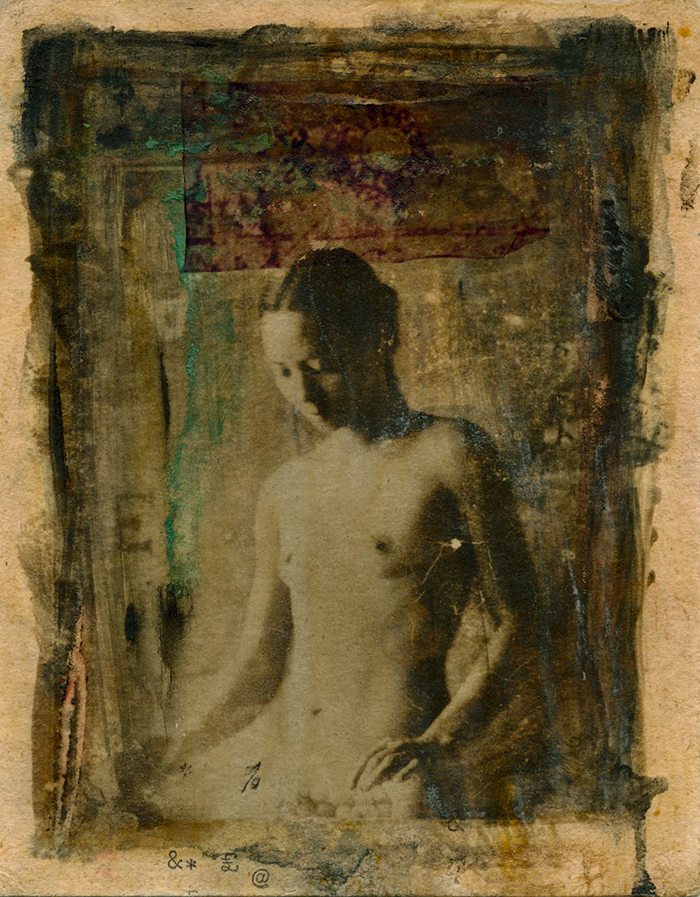

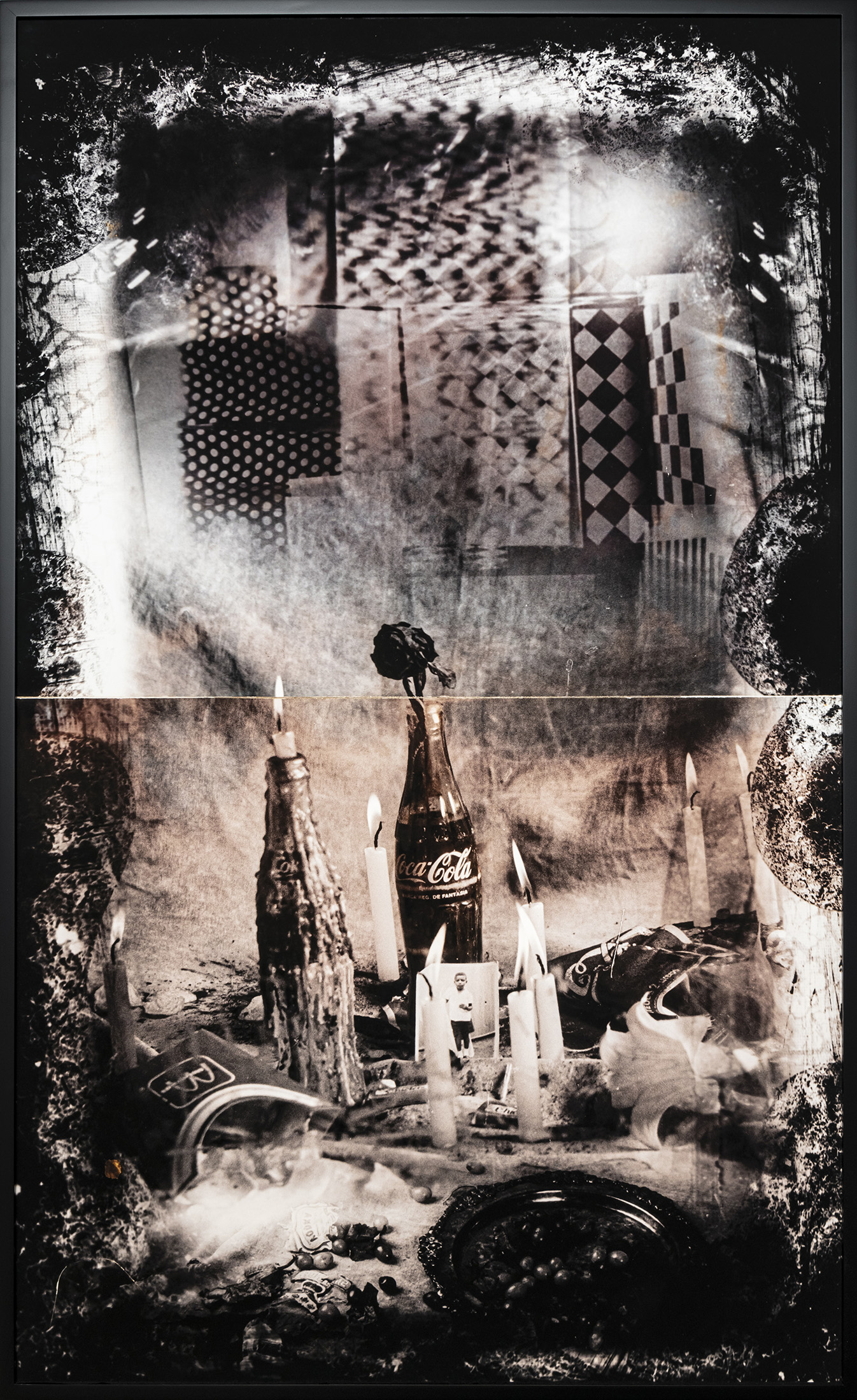

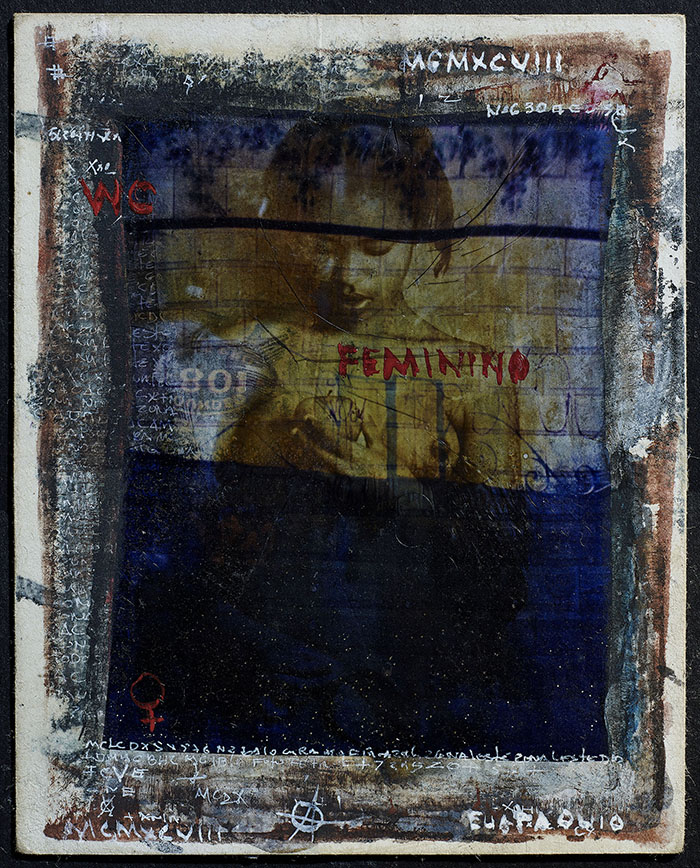

¿Es posible que la mirada de un fotógrafo autodidacta sea diferente a la de un fotógrafo formado? ¿Hasta qué punto la fotografía pierde o gana valor poético si la imagen que persigue busca cierta “perfección” técnica? Es evidente que la obra de Eustáquio Neves (Juatuba, Brasil, 1955), puede ofrecernos una respuesta desde el punto de vista estético y poético de la imagen. Su trabajo transgrede no solo el estatuto del purismo fotográfico a través de técnicas y recursos, sino que su formación autodidacta le ha permitido jugar y experimentar con diferentes métodos, medios y soportes, incluyendo la pintura y la manipulación del negativo, algo que se ha convertido en una especie de marca registrada de su obra, siendo el proyecto “Caos Urbano” de 1992 uno de sus primeros ensayos destacados.

Is it possible that the perspective of a self-taught photographer could be different from that of a trained photographer? To what extent does photography lose or gain poetic value if the image it pursues seeks a certain technical “perfection”? It is evident that the work of Eustáquio Neves (Juatuba, Brazil, 1955) can offer us an answer from the aesthetic and poetic perspective of the image. His work not only transgresses the status of photographic purism through techniques and resources, but his self-taught background has also allowed him to play and experiment with different methods, mediums, and supports, including painting and negative manipulation—something that has become a kind of trademark of his work, with the project “Caos Urbano” from 1992 being one of his first notable explorations.

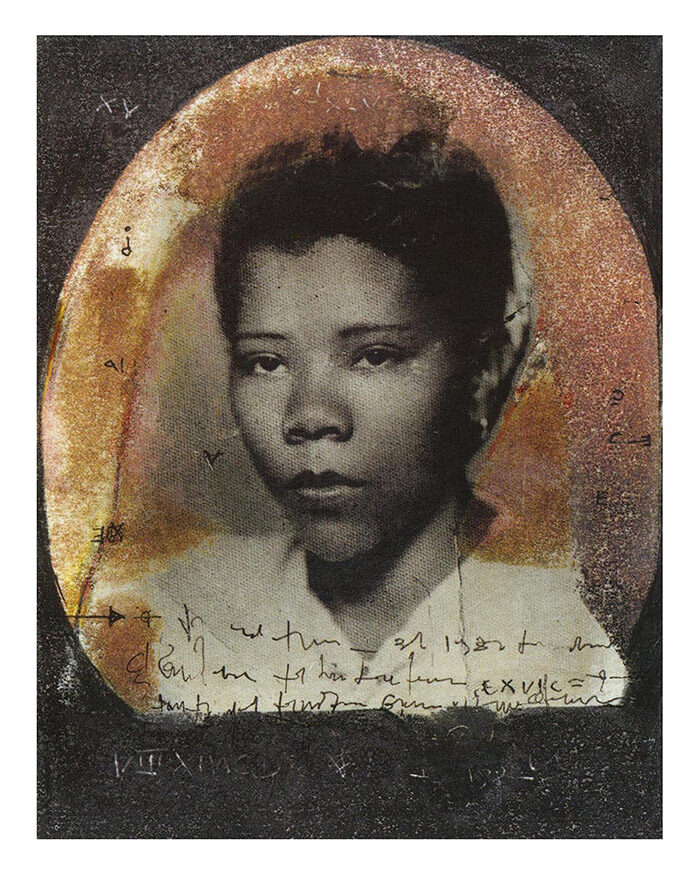

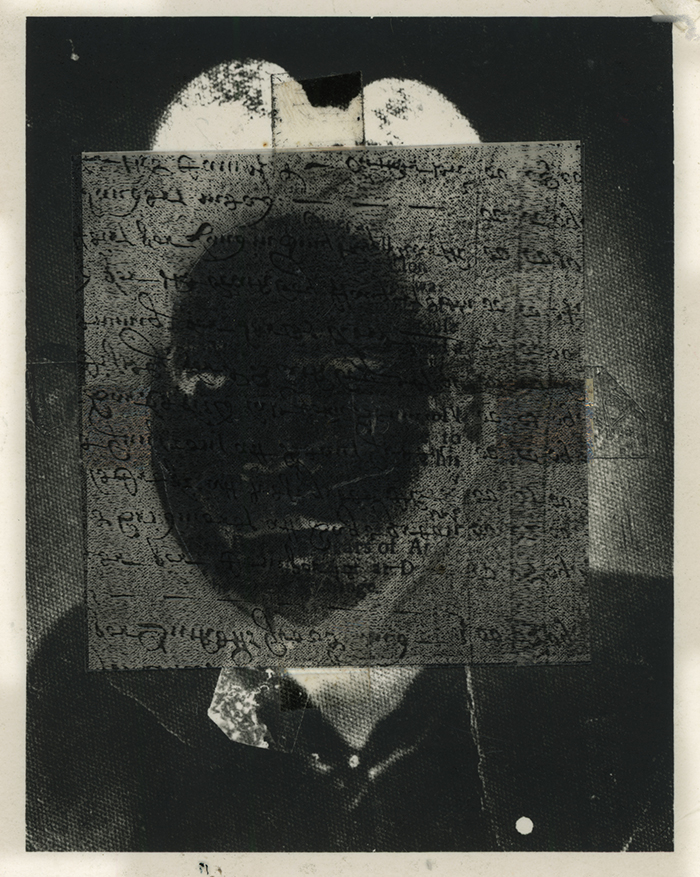

En 1979 se tituló como técnico en Química Industrial, y esta carrera le proporcionó los recursos para la manipulación de negativos fotográficos que luego realizaría en su trabajo como fotógrafo. Asimismo, ha declarado que su aprendizaje de guitarra clásica le ayudó a organizar el montaje de imágenes con métrica y ritmo. En 1987, instaló un pequeño estudio de fotografía en Belo Horizonte, donde se observa otro elemento crucial en su producción: “el lugar del negro en la sociedad brasileña”. En la serie “Punishment Mask” (2004), se refiere a las máscaras metálicas utilizadas como instrumentos de castigo y tortura durante la época de la esclavitud. El fotógrafo utilizó un antiguo retrato de su madre y llevó a cabo varias intervenciones físicas y químicas, incluida la superposición de la imagen de la máscara de metal.

In 1979, he graduated as a technician in Industrial Chemistry, a career that provided him with the resources to manipulate photographic negatives, which he later applied in his work as a photographer. He has also stated that his classical guitar training helped him organize the composition of images with metric and rhythm. In 1987, he set up a small photography studio in Belo Horizonte, where another crucial element in his work becomes apparent: “the place of black people in Brazilian society.” In the series “Punishment Mask” (2004), he references the metal masks used as instruments of punishment and torture during the era of slavery. The photographer used an old portrait of his mother and carried out various physical and chemical interventions, including the superimposition of the image of the metal mask.

Vivimos casi cuatro siglos como esclavos en Brasil y hasta hoy, ciento veintinueve años después de la abolición de la esclavitud, seguimos siendo invisibles para una gran mayoría blanca que parece creer que el país se hizo exclusivamente para ella.

We lived as slaves in Brazil for almost four centuries, and even today, one hundred and twenty-nine years after the abolition of slavery, we remain invisible to a large white majority that seems to believe the country was made exclusively for them.

Su obra aborda temas que reflexionan sobre la discriminación racial, el territorio y las formas en que el ser humano comprende la (su) historia, lo que convierte su trabajo en un interesante híbrido visual y filosófico de la existencia, desde donde explica “el hombre al hombre”, tal como lo escribió Susan Sontag. Además, formalmente experimenta con técnicas de montaje en las que superpone fragmentos de otros negativos, copias de otras imágenes e información verbal sobre las imágenes. Es un trabajo múltiple que incluye la realización de vídeos experimentales, como “Dead Horse” (2009), así como la publicación del libro “Eustáquio Neves”, que apareció en la serie Photoportátil de la editorial Cosac Naify.

His work focuses on themes that reflect on racial discrimination, territory, and the ways in which humans understand (their) history, making his work an interesting visual and philosophical hybrid of existence, from which he explains “man to man,” as Susan Sontag wrote. Additionally, he formally experiments with montage techniques where he overlays fragments of other negatives, copies of other images, and verbal information onto the images. It is a multifaceted body of work that includes the creation of experimental videos, such as “Dead Horse” (2009), as well as the publication of the book “Eustáquio Neves,” which appeared in the Photoportátil series by Cosac Naify.

Eustaquio Neves, quien actualmente es representado por la galería Vermelho, tiene una trayectoria importante que se evidencia en un trabajo potente y sólido, una mirada aguda y disidente, y una mente inquieta. Su obra es reconocida a nivel nacional e internacional y se ha exhibido en lugares como Brasil, Cuba, Estados Unidos, Francia, Malí, Mozambique, Finlandia, entre otros. Tuvo una participación destacada en la 35ª Bienal de São Paulo en 2023, y ha recibido premios como: Premio al Mejor Artista/Fotolibro del Instituto Moreira Salles (2023); Premio Mediterraneum 2022 de Fotografía de Autor; Premio Videobrasil y WBK Vrije Academie, Países Bajos (2007); Gran Premio JP Morgan de Fotografía (1999); y VII Premio de Fotografía Marc Ferrez (1994). Además, su obra forma parte de importantes colecciones a nivel mundial.